People have always died, and for as long as people have died, the disposal of bodies has been required. Various methods have stood the test of time, whether they be burial, cremation, or even being sent off to sea like a Viking warrior. As with these methods, we usually keep bodies out of sight, and memorials such as graves or tombs are instead constructed as a visual reminder. However, sometimes much more creative methods are forged. Under the city of Paris, the capital of France, there are hundreds of miles of secret tunnels and passageways that may give you a bit of a shock.

The Paris Catacombs consist of an underground labyrinth spanning over 200 miles in length. The word “catacomb” derives from the Latin for ‘amongst the tombs’, and these tunnels in Paris are certainly true to this name, as the ossuary houses the skeletal remains of over six million Parisians.

The creation of the catacombs was originally a vital measure for the people of Paris: towards the end of the 18th century, there was a huge public health scare caused by the inner–city cemeteries. Many had been used for hundreds upon hundreds of years, and the bones were piling up – literally. The overflowing of the dead led to many outbreaks of disease and therefore meant that the old cemeteries had to be closed and the remains removed. The main cemetery in Paris at the time, Saints Innocents, was closed in 1780. After the closure, the authorities needed somewhere to dispose of the excess human remains, and they decided to use the former quarries under the neighbourhood of Montrouge, situated two miles from the centre of the city. These quarries are known as ‘Tombe-Issoire’ and date back to activity as early as the 15th century. They were closed in 1776 due to many collapses on the ground level during the early– and mid-18th century. From 1787-1814, the majority of the bones from the overflowing cemeteries were moved to the former quarries, consolidated as underground ossuaries.

The tunnels were first opened to the public in 1809, and are still available for visitation to this day. The first thing that a curious visitor will notice is their vast size. The Denfert-Rochereau Ossuary (the area of the tunnels that is available for public access) is 11,000 square-metres, and has a depth of 20 metres – this approximates to the height of a five-story building. There are 243 steps to walk in total (131 going down, 112 going upwards), and in total there are 1.5km of eerie passageways to travel through. Impressive? Well, given that the catacombs stretch for a total of 200 miles, an official tour isn’t even skimming the surface.

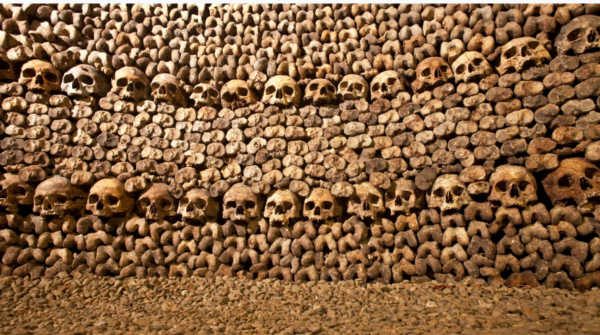

The Catacombs of Paris are exceptionally unique due to their stylization. When the skeletons were removed from Saints Innocents, workers organized the bones into piles, rather than keeping the bodies together. Because the remains were sorted this way, it provided the Director of the Paris Mine Inspection Service, Louis-Étienne Héricart de Thury, the idea of approaching the creation of the ossuaries with a museographical and monumental style. As you can see, Thury made sure that artistic integrity was engrained into the creation of the catacombs. Rows of skulls line the walls, while impressive columns of bones have been constructed in the middle of the caverns. These decorative formations of the dead may seem harrowing at first sight, but upon reflection, the beauty of the human body can still continue long after life has ceased to exist.

Since the tunnels were opened to the public in 1809, they became a very popular attraction within the upper echelons of society, and gained visitors from throughout Paris, the rest of France, and abroad. It is believed to be the burial place for many notable members of French society, as these individuals were buried in the graveyards that bones were removed from. Notable remains include that of Charles Perrault, the author of well-known fairytales such as Little Red Riding Hood (whose version was published before that of the Brothers Grimm), Cinderella, and Puss in Boots; Jean de la Fontaine, famous for a collection of fables; painter Simon Vouet and Baroque sculptor François Giradon. The Paris Catacombs have also had their famous visitors: they have been frequented by French royalty and even Napoléon Bonaparte.

Because such a vast area of the tunnels is uncharted and not (officially) open for public access, they aren’t without their secrets and controversies. In 2004, the French police stumbled across a 500 square metre cavern that was home to a cinema. In this cinema, there were seats where various noir classics and modern thrillers were available for viewing, as well as a fully stocked bar and a working restaurant. On the initial discovery of the cinema, during their journey through the passageways, they were warned off by several signs claiming that building works were occurring and that they should turn around and leave. At one point, there were even recordings of dogs barking to ward off any other curious parties. When the police returned to the cinema for the second time, nothing remained but a note on the floor that read, “Do not try and find us.” There are thought to be many secret societies and sects running throughout the catacombs, home to many bizarre goings on. It is reported that in one area, there is even a pool of water, accessible for a swim!

The underground labyrinth was also the setting of a wine heist in 2017. Thieves used the tunnels to make it underneath a nearby apartment cellar, which they then managed to break into, stealing over 300 bottles of vintage wine valued at €300,000. Someone breaking into your house from underneath is definitely the last thing you would expect, and who knows what other crimes these catacomb thieves have in mind?

The tunnels have been frequented by few, and remain a mystery to many. They were last formally used during WW2, where the French resistance used it to travel the city undetected, and the German army are also known have had a bunker under a high school called the Lycée Montaigne in the 6th arrondissement (administrative district) of Paris.

The outer regions of the Catacombs now remain with a few, avid explorers known as ‘cataphiles’, as well as the mysterious people building cinemas, taking swimming trips, and committing crimes amongst the bones. They are, in essence, a secret society, and would be rather meticulous to infiltrate. I am sure many more bizarre stories from the underground will surface in the years to come.

Although the Catacombs of Paris may seem as if they are a unique phenomenon, they are not the only ones of their kind, nor are they the first. The term “catacomb” was borrowed from the Catacombs of Rome: these underground ossuaries are believed to be the first in existence, and were created in the 2nd century AD. The idea caught on throughout the years and there are now catacombs and other similar corpse constructions in 20 different countries across various continents, including Egypt, the Philippines and the Czech Republic.

The Catacombs of Paris are now visited by half a million people each year. Of course, these are only the official figures for the small area that is open as a tourist attraction. Who knows how many other groups of people – and individuals – are lurking under the streets of Paris amongst the dead?